10. This Sporting Life

Lindsay Anderson brought to bear on his adaptation of David Storey’s first novel, all the poetic-realist instincts he had been honing for the previous decade as a documentarian in the Humphrey Jennings mould. (Anderson had won the 1953 best doc Oscar for Thursday’s Children.) Filmed partly in Halifax and Leeds, but mainly in and around Wakefield Trinity Rugby League Club, one of its incidental attractions is its record of a northern, working-class sports culture that would change out of all recognition over the next couple of decades.

The story of Frank Machin, a miner who becomes a star on the rugby field, all the while knowing that he is considered as disposable property – a machin(e)? – by his club, and as “a great ape on a football field” by his landlady and lover (Rachel Roberts), is told in a stream-of-consciousness style, largely in flashbacks from a dentist’s chair, using some of the most inventive editing – by Peter Taylor – that British cinema had ever seen. Produced by Karel Reisz, it was perhaps the last gasp of the northern kitchen-sink boomlet inaugurated by Room at the Top and climaxing with Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, and its failure at the box-office caused producers to withdraw from the genre.

Nonetheless, this is the movement’s artistic pinnacle, featuring marvellous black and white cinematography by Denys Coop, and performances that are still shattering to witness. Harris was just back from Tahiti, having played opposite Marlon Brando in Mutiny on the Bounty, and although he abhorred Brando, the cursed and luckless Machin – shirt number 13 – is as Brando-esque a performance as British cinema has ever produced.

And though the rugby scenes take up relatively little screen-time, they are vivid, violent and frenetic, with massed crowds of working men roaring on the touchline. The last match, with Harris physically exhausted and emotionally destroyed, and black with mud, is filmed like a day on the Somme. John Patterson

9. Olympia

The Kobal Collection/www.kobal-collection.com

Even after 75 years, Leni Riefenstahl’s document of the 1936 Berlin Olympicsremains controversial; not simply because of its government-sponsored status but because of the chicken-and-the-egg questions it raises about Riefenstahl’s own ideology. Split into two parts, with a near four-hour running time, Olympia begins with a flashback to the original Greek games: in marble ruins, we see statues coming to life, shotputters, discus and javelin throwers. The emphasis on the body beautiful – with some surprisingly bold male nudity – is these days more disturbing than inspiring, recalling Nazi architect Albert Speer’s fondness for Greek classicism and the party’s general obsession with eugenics.

Though it is unmistakably entrenched in Nazi ideology, Olympia has a slightly better PR image than Riefenstahl’s signature work, Triumph of the Will – which covered the 1934 Nuremberg rally – simply because it reflects something more of her documentarian nature. Adolf Hitler, almost a deity in Triumph, is here shown much as any other hosting dignitary might, and the director seems genuinely interested in her subject, presenting what’s happening in front of her rather than trying to stylise it to a pre-existing brief. A case in point is Reifenstahl’s admiring presentation of the year’s Olympic hero Jesse Owens, an African-American track and field athlete whose four gold medals so irked the Führer.

If we disregard the question of intentionality, however, it is clear that Olympia is a work crafted by an extraordinary film-maker, one whose ideas wildly exceeded the simple propaganda demanded by her paymasters. Many of Riefenstahl’s techniques – aerial shots, smash-cuts and especially her use of thundering music – have been appropriated by Hollywood, and as a practical study guide, Olympia can hardly be bettered in its portrayal of sport as a communal and noble pursuit, capturing athlete and audience alike. Unfortunately, Olympia will never be seen simply as art; it is too rooted in the darkest times of 20th-century history for that.Damon Wise

8. Slap Shot

Allstar/Cinetext/UNIVERSAL/Allstar/Cinetext/UNIVERSAL

Slap Shot is not only the best movie ever made about ice hockey (Mighty Ducks can go duck itself), it’s also one of the best movies about the declining rustbelt of the 1970s, as it makes its way through any number of broke and moribund industrial cities. The Charlestown Chiefs are a low-grade, minor-league team in a Pennsylvania town whose largest mill, employing 10,000 workers, is due to close, essentially killing off the town’s economic base. Coach and player Reggie Dunlop (Paul Newman) learns that this may be the team’s final season and goes to war with his own manager (champion sleazebag Strother Martin) to try and unearth the team’s anonymous owner. In the meantime, he and the team resort to showbiz tactics to score some ink and build up their name, hiring the Hanson brothers, three bespectacled, childlike super-thugs, and making damn sure that there’s a good punch-up or 10 in every game.

Raw, cynical and unendingly funny, Slap Shot was also just about the sweariest Hollywood movie ever made until that point (its main competitor in this regard was Hal Ashby’s The Last Detail), and the censored network TV version was possibly the first time we ever heard the now ubiquitous fake-swear-word “fricking”. Dunlop is a conman, a cheat, a womaniser, a cynic and yet somehow, still an idealist. He loves his town, but sees it is dying, and is determined to give the fans and the team one last chance at something not unadjacent to glory. Failing that, he’ll settle for another ice-fight.

And he gets it, in the climactic encounter with the ferocious Syracuse Bulldogs and their line-up of specially recruited brutes, criminals and apes, a game that ends in chaos, with the Chief’s top scorer (Michael Ontkean) stripping down to his jockstrap on the ice as the hometown crowd goes nuts. JP

7. Bull Durham

Allstar/Cinetext Collection/Sportsphoto/Allstar/Cinetext Collection

Ron Shelton’s 1988 baseball movie is principally known these days for first introducing the liberal Hollywood It couple Tim Robbins and Susan Sarandon, which is an indication that this does follow not the usual macho one-last-touchdown trajectory that characterises most US sports stories. In fact, Bull Durham is not only a movie in which the mechanics of baseball don’t really matter at all; it is, most unusually, about the unfairness of sport, going so far as to suggest in its love-story subplot that a good relationship may be the best success of all.

Kevin Costner stars as “Crash” Davis, an experienced player brought in by the Durham Bulls to train the talented but undisciplined Ebby LaLoosh (Robbins). Davis’s job is to raise his game, a task that is shared by new age baseball groupie Annie Savoy (Sarandon), an older woman who adopts LaLoosh as her lover. Between these three a love triangle ensues, although Sarandon keeps us guessing as to whom the smarter-than-she-first-seems Annie will eventually choose.

While it was seen as a star vehicle for Costner, then achieving A-list status in the run-up to his self-directed Oscar hit Dances With Wolves, Bull Durham is also notable for turning supporting player Robbins’s fortunes around almost overnight as the unpredictable and really rather stupid LaLoosh. It is here that Shelton’s film stands out; although the grizzled-mentor-and-ungrateful-student storyline would soon become standard (ground recently covered by Clint Eastwood in Trouble With the Curve), Bull Durham explicitly addresses the ruthless nature of commercial sport. It is also, for a sports movie, perhaps unique in that it dispenses almost totally with the usual character arcs: at the end, there is no Damascene fist-punch moment, just the quiet realisation that these people will never be transformed by winning: they will always be who they really are. DW

6. Point Break

20thCFox/Everett/Rex Features

“Young, dumb and full of cum” – that’s one character’s summary of rookie FBI agent Johnny Utah, hero of Point Break, and it’s an insult that also stuck for a long time to Keanu Reeves, the actor playing him. But no one could accuse Kathryn Bigelow’s movie of stupidity. Call it bizarre by all means: it concerns, after all, a troupe of daredevil surfing hippies, led by the mystical Bodhi (Patrick Swayze), who moonlight as bank robbers in ex-president masks. And it certainly flirts with cliche in its exploration of the buddy movie dynamic between Bodhi and Johnny, who infiltrates the group and is drawn into the highfalutin’ poetry of surfing. There’s plenty of campness too, not least in the camera’s fawning relationship with Reeves, and the way in which Lori Petty, as his ostensible love interest, loses out time and again to him in the battle for adoring close-ups.

But what pulls Point Break through is Bigelow’s sincerity. There’s no hint of mockery in her approach to Bodhi and his philosophy, or to his increasingly homoerotic relationship with Johnny. (The film’s poker face is one of the things that lends it so readily to spoofing – see Hot Fuzz, or the Los Angeles cult theatre hit Point Break Live!) Long before The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty, Bigelow had already established herself here and in her earlier work as a master of genres once deemed exclusively male. She’s a dab hand at pace, switching with ease from the contemplative beachfront serenity of the surfing sequences and the wham-bam action set-pieces (including a daring sky-dive and a breathless chase, shot on hand-held camera, during which Reeves almost has his pretty face lawn-mowered off his skull). But she brings something else that is rare in action movies: an interrogative sensibility, picking over the conventions of genre even as she is serving them up to us on a gleaming platter. Ryan Gilbey

5. Jerry Maguire

Andrew Cooper/Associated Press

Great sports movies bring us the people behind the big moments, allowing us a thrill of victory for players and teams who don’t even exist. Jerry Maguire brings us the people behind the people behind the big moments, the ruthless and shameless agents who scramble for a 4% share of their million-dollar talents. Jerry becomes our hero when he stays up late writing a manifesto, laying out the way that his industry can actually care about its clients – and getting fired for his efforts. But Cameron Crowe’s film is about watching Jerry earn that hero status, casting Tom Cruise in his quintessential role – the cocky schemer – and forcing him to become a human being

Crowe could have set a story about a callow businessman finding his soul in virtually any industry, but it’s especially elegant behind the scenes of professional football, the most popular and profitable sport in America. Billions of dollars are spent and agents are hired to take the guessing out of the sport, but it’s always complicated by people, whether it’s the dim recruit Cush choosing another agent over Jerry or Cuba Gooding Jr’s explosive Rod Tidwell playing poorly because he’s upset about his contract. There’s only one climactic game in Jerry Maguire because it’s all about the moments in getting there, from the instantly famous shout of “Show me the money!” to Jerry’s complicated marriage to Renée Zellweger’s Dorothy, the single mum who stands by him while he rebuilds his world.

Crowe may be the most humanist writer-directors currently working, and it’s the uniformly fascinating humans of Jerry Maguire – even the adorable moppets actually pull their weight – who make the film rich and alive. In Crowe’s hands an $11.2m contract is a well-deserved triumph. A touchdown is a chance for reunion and redemption. In Jerry Maguire, the richest sport in America is about its people again. Katey Rich

4. The Wrestler

Rex Features

As Randy “the Ram” Robinson, a burnt-out wrestling star scratching a living on the old pros’ circuit, Mickey Rourke found the role of his career at the age of 52 in The Wrestler. Randy fits him like a glove – or, in this case, like a pair of ill-advised Lycra strides. Early in the picture, a doctor gives Randy a choice: quit wrestling or die. Reluctantly, he slows down. He takes a supermarket job, cosies up to an ageing stripper, Cassidy (Marisa Tomei), and seeks out his estranged daughter, Stephanie (Evan Rachel Wood). But then a promoter reminds him of one of his classic 1980s bouts, the Ram v the Ayatollah: “Two words: Re. Match.”

The Wrestler represented a comeback not only for Rourke, but for the directorDarren Aronofsky, who was coming off a nasty bruising of his own after his largely unloved science-fiction project The Fountain. Both seemed revived by their collaboration, which brings vigour and grittiness to the sort of standard redemption story much favoured by the sports genre. Randy is not so much a role as a tap from which pathos might flow at any moment. But the actor, who was Oscar-nominated for his work here, stays fully in check. He doesn’t strain to project a damaged past now that his physiognomy tells that tale all too eloquently. His face is simultaneously spongy and blunt: half blancmange, half snowplough. His lilting, feminine voice is still audible, but it’s buried deep inside a rasp that suggests a gravedigger’s shovel scraping on tarmac. There’s also a poignant overlap between actor and role. Let’s not pretend that some autobiographical pain isn’t seeping into the picture when Stephanie screams: “You are a living, breathing fuck-up!” What are the chances Rourke has heard that one before? RG

3. Hoop Dreams

Ronald Grant Archive

Over the course of five years, three film-makers followed two African-American teenagers pursuing one dream: to become stars of the basketball court. But while Hoop Dreams, directed by Steve James, Frederick Marx and Peter Gilbert, shows the sport itself in detail, it is also, like any good sports movie, more concerned with the larger social ramifications and symbolism. Arthur Agee and William Gates, two 14-year-olds from Chicago housing projects, seem to have the hoop-shooting skills necessary to propel themselves far from their inauspicious beginnings. But as the film reveals slowly and meticulously, there are other obstacles ahead, from the domestic and academic to the financial. It’s all very well landing scholarships to the privileged, and predominantly white, St Joseph high school; but there are still economic traps awaiting them there, not to mention the increasingly fearsome coach, Gene Pingatore (who later sued the film-makers over the picture’s unflattering portrayal of him). From ages 14 to 19, we see Agee and Gates growing and struggling under the weight of their own dreams and other people’s. “All my dreams are in him now”, says Gates’s brother at one point. “I want it so bad I don’t know what to do.”

Although Hoop Dreams did not want for acclaim when released in 1994, it was the victim of a voting snafu at the following year’s Academy awards, where an imperfect nomination process led to it being snubbed in both the best picture and best documentary categories. (That very omission later led to the revision of the voting system.) History has been kinder. The late Roger Ebert picked Hoop Dreams as the best film of the 1990s. And it is widely recognised as not only one of the greatest sports movies ever made, but one of the most expansive and compassionate documentaries of all time. RG

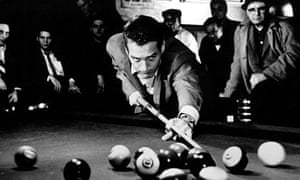

2. The Hustler

Rex Features

Director Robert Rossen made three classic movies: the boxing picture Body and Soul, the best of its kind until Raging Bull, the definitive 1949 version of All the King’s Men, and his enduring masterpiece, The Hustler, in 1961. An instant classic upon its release, it was responsible for reinvigorating the sport of pool, and spawned an excellent sequel by Martin Scorsese, The Colour of Money, starring Newman and Tom Cruise, in 1986

Newman is “Fast Eddie” Felson, a prodigy with the cue-stick who’s determined to take on the legendary Minnesota Fats (Jackie Gleason in a wonderfully restrained and authoritative performance). This he does in a bravura opening section, winning thousands of dollars off Fats in a marathon all-night contest, but walking away with nothing but his original $200 stake. In the meantime he’s taken up by the vile and unscrupulous gambler-manager Burt Gordon (one of George C Scott’s greatest early performances), who considers Eddie a great pool player but a born loser at heart. He also gets involved with a limping, alcoholic young college drop-out played by the mesmerising, Oscar-nominated Piper Laurie, who would disappear from the movies almost immediately afterwards, not to be seen again until she played the psychotic mother of Brian De Palma’s Carrie 15 years later, another indelible performance.

The journey Fast Eddie takes, through scuzzy pool halls, bus stations, poker schools and gilded southern mansions (all captured by cinematographer Eugen Shufftan, who shot Lang’s Metropolis and Gance’s Napoleon), costs him every last thing he has: mobbed-up poolroom hustlers break his thumbs, his girl is driven to suicide by the loathsome Gordon, and he’s finally warned never to enter a pool hall again, or lose his life. This is Newman’s greatest performance; he is young, beautiful, fatally arrogant and in some fashion quite existentially doomed – and he really can shoot pool. JP

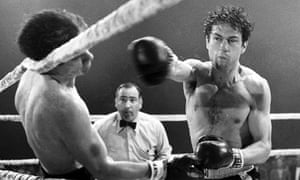

1. Raging Bull

Rex

“Now, sometimes, at night, when I think back, I feel like I’m looking at an old black-and-white movie of myself. Why it should be black-and-white, I don’t know, but it is. Not a good movie, either, jerky, with gaps in it, a string of poorly lit sequences, some of them with no beginning and no end.”

The author is former middleweight boxing champion Jake LaMotta, in his 1970 autobiography Raging Bull: My Story, a book which Robert De Niro discovered and brought to the attention of Martin Scorsese in 1974. Was the “movie” analogy LaMotta’s own idea? It could have been put into his mouth by his ghost-writers: Pete Savage, a grindhouse movie producer who had actually cast LaMotta in a couple of low-budget films before this – or Joseph Carter, a journalist and art historian who, intriguingly, had published a study of Italian Renaissance painting. Either way, the spark of cinephilia and visual sense was there from the very beginning. LaMotta’s own avowed sense of his life as a mysterious and chaotic black-and-white movie (a home movie? A stag movie?) was brilliantly transformed into Scorsese’s great work, perhaps his greatest.

De Niro is electrifyingly and horribly charismatic in the role of the toxic champ. In real life, he was a graceless brawler in the ring and outside it, a repugnant killer, bully and wife-beater who was in thrall to the mob. The film actually suppresses many of the nastier aspects of LaMotta’s life: it removes the murder he committed as a young man and essentially takes Jake at his own lenient estimation of himself, emphasising what was allegedly his initial resistance to gangsters’ parasitic involvement in his career. The effect is to combine brutality and self-destruction with a lethal, even outrageous sentimentalism and self-pity.

Critics often talk about “guilt” in Raging Bull: actually, De Niro’s LaMotta never feels guilty: even when he’s begging his wife Vikki not to leave after he’s hit her – it’s just whining and needling. LaMotta feels a little shame, a lot more indignation, much self-righteousness and a volcano of rage.

The episodes of his life are captured in dreamlike, pin-sharp monochrome cinematography, stark images reproduced like a Weegee crime scene. The result is operatic and compelling. Like most boxing movies, there is no sense of the technique of boxing, no sense of how precisely LaMotta was “scored” by his judges in the absence of a knockout – though it is his furious refusal to accept the judges’ decision in that extraordinary opening sequence which is to show us his crazy arrogance and insecurity.

The fight sequences themselves, with the camera swirling and swooping around the ring, and the soundtrack sometimes gulping out into silence and sometimes moaning with weird half-heard animal noises, are extraordinary: an inspired reportage recreation in the manner of a Life magazine shoot, which also looks like expressionist newsreel footage of a bad dream. The punch-ups that break out in the crowd at that first fight; the screaming woman trampled underfoot, glimpsed and then instantly forgotten about; it is profoundly disturbing.

Raging Bull brilliantly and persuasively shows its lead character getting older. Young LaMotta in the ring and old LaMotta on the skids, pensively going through his monologue routine in the dressing room before his night club act: they are the same person, yet different, and of course this was partly because of the weight famously De Niro piled on for the part.

The young fighter is tense, moody, seeming almost to vibrate like a plucked guitar string: he erupts with anger, which then morphs either into sullen resentment or giggling mockery, as if it is his victims are behaving absurdly. He is furious that his sparring-partner brother Joey has invited local wiseguys to the gym to watch him train without his permission: he suspects, correctly, that they want his money. Jake brutally attacks Joey in the ring, and then giggles and jeers at Joey’s angry and deeply wounded response.

Conversely, LaMotta will find himself self-consciously seated at nightclubs or restaurants, uneasily aware of the new pressures of celebrity, accepting the proffered handshakes of fans or gangsters negligently, with a wince of polite impatience or discomfiture. It is on such an occasion that he first glimpses and falls in love – or lust, or acquisitive carnal insanity – with Vikki. Unforgettably, the sound and hubbub of the club will dwindle almost to silence: only the plink-plink-plink of the bass line from the band.

Old LaMotta is quite different: the former fighter turned nightclub turn. With an audacious absence of method affect, De Niro drones his way through Brando’s On the Waterfront speech, rehearsing his set, while thoughtfully puffing his cigar. Actually, De Niro does a much stronger Brando impression elsewhere in the film, intentionally or not. Young Jake confesses to his brother his darkest anguish: “No matter how big I get … I ain’t never gonna fight Joe Louis.” That nasal, glandular whine: for a moment, it is pure Brando.

Joe Pesci is superb as Jake’s pugnacious, exasperated brother and manager Joey. Frantic with worry and impatience at first; later he appears older, balder, with a thin moustache, utterly unable to respond to Jake’s boorish attempts to effect a tearful reconciliation in the street. Unlike Charley in On the Waterfront, Joey is the brother who really is, for his sins, looking out for Jake. He gets him a championship shot. But first of course Jake must, in the time-honoured fashion, take a dive. At the height of his prestige, he has to be matched with a patsy on whom bookies’ odds are sky-high. The mobsters bet big on the no-hoper and Jake has to lose. In return, the wiseguys will arrange for a title fight.

This grotesque ordeal for Jake is at the very centre of the film’s meaning. It isn’t simply about the money: it is a dysfunctional, abusive ritual in which he has to be emotionally mutilated like a gelding by his sneering mob sponsors. Jake sobs hysterically in the dressing room after the farcical fight, clearly mortified that he has failed to make his defeat look convincing by straightforwardly hitting the canvas: as ever, his pride would not permit him to go down, so he found himself enduring a drawn-out ordeal in which he was apparently outboxed over the full distance by an obvious no-hoper, while the booing from the incensed crowd became deafening.

But actually, the point is that the “dive” will always look bad. Like all contenders, Jake has to be humiliated, shown who’s really in charge. He must bow the knee to east coast mafia boss Tommy Como, played by Nicholas Colasanto, who in his creepy avuncular way paws and slobbers over Jake’s wife Vikki, played by Cathy Moriarty, in his hotel suite before the fight. After Tommy has gone, Jake screams abuse at Joey and Vikki, whom at the height of his paranoia he will suspect of having an affair.

Cathy Moriarty is tremendous as Vikki; like Jake’s first wife she is utterly bemused and disgusted and scared by his behaviour, and simmering also with self-reproach at having put up with it for as long as she has. Yet Vikki’s first date with Jake at a crazy golf course is an extraordinarily romantic sequence: the clear sunlit sky of this atypical outdoor scene shows up like a sugary-wet expanse of pale grey across the screen.

It is so weirdly innocent, even while it crackles with sexual tension, and while Jake casually acknowledges the existence of his wife who he says must be “out shopping” when he takes Vikki back to the apartment. Jake meets Vikki first while she is hanging out at the swimming pool: a superbly managed, unhurried sequence, rippling and shimmering with erotic languour and yearning.

It probably makes little sense to think of Raging Bull as a “sports movie” or a “boxing movie”. Raging Bull goes beyond this and Jake is not a Rocky-Balboa-style underdog. Winning and losing become irrelevant in the neurotic chaos of fighting: fighting with the mob, with his brother, with his wives, with himself. LaMotta’s boast is that no one ever got him down. It is an empty boast from a bruised and bloody zombie trapped in his own male rage. Peter Bradshaw